Science

Earth’s ozone layer hole over Antarctica is bigger than usual this year, researchers say

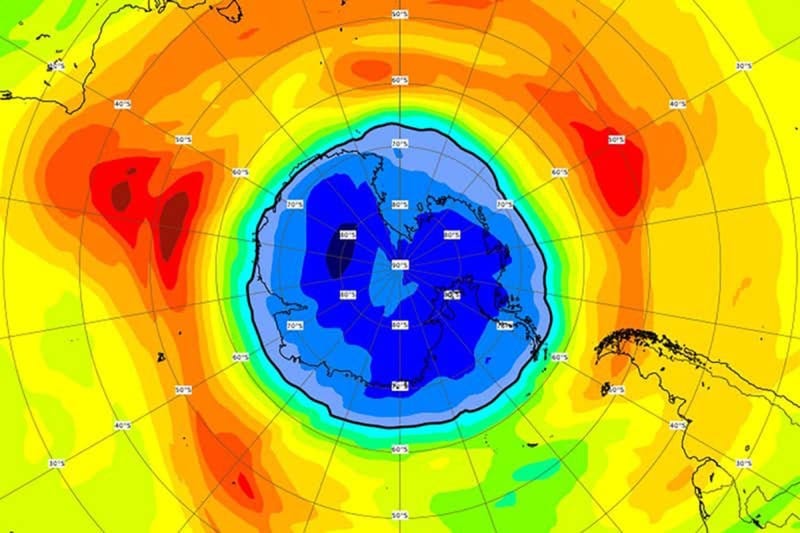

Researchers say the hole in the Earth’s protective ozone layer over the Southern Hemisphere is bigger than usual this year and as of now outperforms the size of Antarctica. The hole in the ozone layer that grows every year is “rather larger than usual” and is as of now greater than Antarctica, say the researchers liable for monitoring it.

The European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service said that the so-called ozone hole, which shows up every year during the Southern Hemisphere’s spring, has grown impressively in the previous week after an average beginning.

The hole in the ozone layer over the South Pole is presently bigger than the size of Antarctica, as indicated by forecasters.

Researchers reported on Thursday that after a “pretty standard” start to 2021, the ozone hole became outstandingly greater this previous week. It is presently bigger than 75% of ozone holes at this stage in the season since 1979.

The ozone layer is the thin part of the atmosphere that shields life on Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. In humans, this can cause health problems like skin cancer and eye harm while likewise impeding plants’ ability to absorb carbon, a significant part of mitigating the climate emergency.

Scientists from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service say that the current year’s hole is developing rapidly and is bigger than 75% of ozone holes at this stage in the season since 1979.

Ozone exists around seven to 25 miles (11-40km) above the Earth’s surface, in the stratosphere, and acts like sunscreen for the planet, protecting it from ultraviolet radiation. Every year, a hole forms during the late winter of the southern hemisphere as the sun causes ozone-depleting reactions, which include chemically active forms of chlorine and bromine derived from human-made compounds. In a statement, Copernicus said that the current year’s hole “has evolved into a rather larger than usual one”.

Vincent-Henri Peuch, the service’s director, told: “We cannot really say at this stage how the ozone hole will evolve. However, the hole of this year is remarkably similar to the one of 2020, which was among the deepest and the longest-lasting – it closed around Christmas – in our records since 1979.

“The 2021 ozone hole is now among the 25% largest in our records since 1979, but the process is still underway. We will keep monitoring its development in the next weeks. A large or small ozone hole in one year does not necessarily mean that the overall recovery process is not going ahead as expected, but it can signal that special attention needs to be paid and research can be directed to study the reasons behind a specific ozone hole event.”

A stratospheric hole shows up annually during the Southern Hemisphere’s spring from August to October. (An hole can sometimes likewise show up over the Arctic region between March and May.)

The 2021 hole seemed to surprise forecasters from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), part of the EU-funded, Earth observation programme.

“This year, the ozone hole developed as expected at the start of the season. It seems pretty similar to last year’s, which also wasn’t really exceptional in September, but then turned into one of the longest-lasting ozone holes in our data record later in the season,” CAMS Director Vincent-Henri Peuch, who heads the EU’s satellite monitoring service, said in a statement.

“Now our forecasts show that this year’s hole has evolved into a rather larger than usual one. The vortex is quite stable and the stratospheric temperatures are even lower than last year. We are looking at a quite big and potentially also deep ozone hole.”

Atmospheric ozone ingests bright light coming from the sun.

Its nonappearance implies a greater amount of this high-energy radiation arrives at the Earth, where it can hurt living cells.

Mr. Peuch noticed that last year’s ozone hole likewise began unexceptionally however at that point transformed into one of the longest-lasting ones on record.

The Montreal Protocol, signed in 1987, prompted a prohibition on a group of chemicals called halocarbons that were faulted for worsening the annual ozone hole.

Specialists say that, while the ozone layer is starting to recuperate, it’s probably going to take until the 2060s for the ozone-depleting substances used in refrigerants and spray cans to vanish from the atmosphere.

Researchers acknowledge that the depletion in the ozone layer is brought about by human-made gases called CFCs, which were first evolved during the 1930s for use in refrigeration systems and were then sent as propellants in aerosol spray cans. The chemicals are steady so can travel from the Earth’s surface to the stratosphere.

However at that point, at the altitude where stratospheric ozone is discovered, they are separated by high-energy UV radiation. The resulting chemical reactions destroy ozone. CFCs have been prohibited in 197 countries around the world.

Since the ban on so-called halocarbons, the ozone layer has given indications of recuperation, yet it is a slow process and it will take until the 2060s or 70s for a total eliminating of the depleting substances. During recent years with normal weather conditions, the ozone hole has commonly developed to a maximum of 20 million sq km (8 million sq miles).

The 2020 Arctic ozone hole was additionally exceptionally enormous and deep, and crested at three times the size of the continental US.

The Antarctic ozone hole usually arrives at its peak between mid-September and mid-October. At the point when temperatures begin to ascend high up in the stratosphere in late southern hemisphere spring, ozone depletion eases back, the polar vortex debilitates lastly separates, and, by December, ozone levels typically get back to normal.

Complex meteorological and chemical processes are behind annual ozone hole formation. CAMs reports that in the South Pole, temperatures high up in the stratosphere start ascending around October, which eases back ozone depletion. Before the year’s over, levels are ordinarily gotten back to normal.

During the 1970s, it was found that ozone layer thinning was being dramatically more awful by human use of halocarbons – chemical substances found in products like refrigerators, packaging, and aerosols.

Every one of the 198 member states of the United Nations signed the Montreal Protocol of 1987 to ban the chemicals.

Research last month recommended exactly how important that international agreement was: the proceeded with use of halocarbons would have added 2.5C to average global air temperatures by 2100. Furthermore, that is on top of extra heating from other greenhouse gas emissions.

“We would be facing the reality of a ‘scorched Earth'” situation, scientists wrote.

Dr. Paul Young, from Lancaster University and the study’s lead author, revealed to The Independent that “it would likely have been pretty catastrophic”.

16 September is assigned as the International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer, to mark that turning point.

Since halocarbons were restricted, it has been in a slow recovery. Researchers say it will take up to the 2070s to see a total phasing out of ozone-depleting substances.

-

Sports4 weeks ago

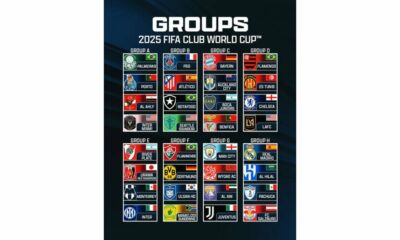

Sports4 weeks agoFIFA Club World Cup 2025: Complete List of Qualified Teams and Groups

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoAl Ahly vs Inter Miami, 2025 FIFA Club World Cup – Preview, Prediction, Predicted Lineups and How to Watch

-

Health1 week ago

Back to Roots: Ayurveda Offers Natural Cure for Common Hair Woes

-

Tech2 weeks ago

Tech2 weeks agoFrom Soil to Silicon: The Rise of Agriculture AI and Drone Innovations in 2025

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoFIVB Men’s Volleyball Nations League 2025: Full Schedule, Fixtures, Format, Teams, Pools and How to Watch

-

Startup3 weeks ago

Startup3 weeks agoHow Instagram Is Driving Global Social Media Marketing Trends

-

Television4 weeks ago

Television4 weeks agoTribeca Festival 2025: Date, Time, Lineups, Performances, Tickets and How to Watch

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoWorld Judo Championships 2025: Full Schedule, Date, Time, Key Athletes and How to Watch