Business

Gopal Balakrishnan on The Concept of Capital in Grundrisse

By Gopal Balakrishnan

The theoretical schema of Grundrisse hinges on the derivation of the concept of capital from that of money: “it is inherent in the concept of capital — in its origin—that it begins with money, and therefore with wealth in the form of money. It is likewise inherent in it that it appears as emerging from circulation, as the product of circulation. Capital formation does not therefore arise from landed property (it could only arise from a tenant farmer in so far as he is also a trader in farm produce), nor from the guild (though the latter also provides a possibility), but from merchants’ and usurers’ wealth.”

Visit https://gopalbalakrishnan.net/ for more insight from Gopal Balakrishnan

This scenario of primitive accumulation was logically entailed by its monetary conception of capital and would come to be supplanted by a narrative of the agrarian origins of capitalism corresponding to his later commodity-based theorization of the nature of capital. The idea behind the agrarian origins of capitalism thesis is that the social property relations which impose the compulsions of exchange dependency on producers and the whole pattern of economic development which flows from this must begin with agriculture because it must sever the vast majority of pre-capitalist society who produce food for their own subsistence from their direct access to the earth.

The analysis of the original formation of capital proposed here deepens the stagist account proposed in The German Ideology but does not fundamentally depart from it. In the writing from this period, precious metals act as a vanishing mediator between the amassing of pre-capitalist wealth through mercantilist plunder and the onset of self-sustaining capitalist accumulation. As ever more products became exchangeable for money, both merchant capitalists and the states that promoted their interests aggrandized themselves by manipulating the terms of trade. In its blood-splattered origins, emergent bourgeois society recognized money as the supreme being of wealth. The ever-wider recognition of hard cash as the general value essence of the proliferating varieties of riches liberated individuals from the constraints of both nature and tradition, making it possible to continuously labor for exchange. Limitless private accumulation becomes the telos of all production, spurring a new temporal regimentation of everyday life.

“Here, money as an end becomes the means to general industriousness. General wealth is produced in order to seize hold of its representative. In this way, the real sources of wealth are opened up. Since the aim of labor is not a particular product that bears a particular relation to the particular needs of the individual, but money, wealth in its general form, the industriousness of the individual firstly has no limits. It is indifferent to its particularity and assumes any form that serves the aim; it is inventive in the creation of new objects for social need, etc.”

Grundrisse’s emphasis on the role played by the cultural liberation of greed in the original formation of capital is arguably symptomatic of absence of a social-relations-based explanation for the onset of a new pattern of labor-time reducing socio-economic development. In this respect one might read these passages of the notebooks in the light of Max Weber’s later thesis that modern capitalism was spawned by a new religious ethos of accumulation. While the sociologist sharply opposed the thirst for acquisition to the Calvinist contempt for temporary and transient pleasures, Marx squarely identified one with the other.

“The cult of money has its corresponding asceticism, its renunciation, its self-sacrifice — thrift and frugality, contempt for the worldly, temporary and transient pleasures; the pursuit of eternal treasure. Hence the connection of English Puritanism or also Dutch Protestantism with money-making.”

The monetary theory of capital, which Marx is seeking to construct in Grundrisse, was formulated in opposition to the classical viewpoint according to which real wealth took the exclusive form of consumable use values. During this intermediate period, as I have designated it, Marx believed that the critique of modern political economy would partly rehabilitate long discredited Monetarist-Mercantilist notions of the relation between money and capital.

“Political economy errs in its critique of the monetary and mercantile systems when it assails them as mere illusions, as utterly wrong theories, and fails to notice that they contain in a primitive form its own basic presuppositions. These systems, moreover, remain not only historically valid but retain their full validity within certain spheres of the modern economy. At every stage of the bourgeois process of production, when wealth assumes the elementary form of commodities, exchange value assumes the elementary form of money, and in all phases of the production process wealth for an instant reverts again to the universal elementary form of commodities. The specific functions of gold and silver as money, in contradistinction to their functions as means of circulation and in contrast with all other commodities, are not abolished even in the most advanced bourgeois economy, but merely restricted; the monetary and mercantile systems accordingly remain valid.”

Although he credited Smith and Ricardo with having represented the anatomy of the real economy with their abstract conception of value and labor, their bracketing of all its monetary forms led them to efface the specifically capitalist character of this real economic process. The admiration he expresses here for the Scotsman James Steuart is telling, as there is hardly a trace of it in Capital, where, by contrast, Smith, Ricardo, and Quesnay stand out in the pantheon of ‘classical political economy’- a term he coined after finishing Grundrisse. The monetary conception of value Marx sets forth in Grundrisse was informed by the work of this now forgotten late Mercantilist writer who had theorized the link between the dissolution of the Scottish feudal-clan order and export-driven primitive accumulation. He quotes Steuart and then goes on to explain his significance in the history of political economy.

““Labor…which through its ALIENATION creates A UNIVERSAL EQUIVALENT, I call industry.”(Principles of Political Economy). He distinguishes labor as industry not only from concrete labor but also from other social forms of labor. He sees in it the bourgeois form of labor as distinct from its antique and mediaeval forms. He is particularly interested in the difference between bourgeois and feudal labor, having observed the latter in the stage of its decline both in Scotland and during his extensive journeys on the continent.”

How Labor Became Capital

In Grundrisse, Marx explains why the technical conditions of production- the instrument, material and agent of labor- come to be equated with the historically specific social relations within which they come to be encased- its instruments and materials being represented by the capitalist and landlord who own them, with its agent appearing as if by necessity as a wage-dependent laborer. His critique of what he would later call the fetishism of capital took on a two-fold form: on the one hand, he sought to sharply differentiate the social-class relations from productive functions in a way that accentuated the primacy of the former as a specification of historically distinct forms of society. On the other hand, he argued that the emergence and reproduction of these historically specific relations of production were dependent upon a level and ongoing dynamic of the development of the productive forces: “the particular specificity of the relation of production, of the category — here capital and labor — becomes real only with the development of a particular material mode of production and a particular stage of development of the industrial productive forces.”

Over the course of its development, capital absorbs the social powers of production which develop within and between all the specialized branches of the division of labor, even those which it did not directly contribute to developing but which it swallows up with great relish. He would later call this process the ‘subsumption’ of labor under capital, highlighting the conditions under which social reality comes to conform to these general categories. The completion of this subsumption of the powers of social production makes capital appear as an indispensable technical factor of production-how could one produce without capital, when the latter is supposedly nothing but the means and materials of production?

Misunderstanding of the labor theory of value had led to a sterile ideological controversy between those who held that labor alone created value and those who objected that capital too contributed to its formation. Marx advanced a third position.

“Those writers, therefore, who demonstrate that all [III-16] the productive power ascribed to capital is a misplacement, a transposition of the productive power of labor, forget precisely that capital is itself essentially this misplacement, this transposition, and that wage labor as such presupposes capital, which is, therefore, this TRANSUBSTANTIATION also from the viewpoint of wage labor; the necessary process for wage labor to posit its own powers as alien to the worker.”

This transubstantiation- i.e., subsumption- constitutive of the alien power of capital over a wage-dependent labor force is consolidated by ever more massive capitalist investment in the burgeoning powers of techno-science, leading to an eclipse of human-directed labor processes. As the level of scientific knowledge required in labor process rises, it becomes increasingly crystallized in the means of labor in the form of fixed capital advances.

“The accumulation of knowledge and skill, of the general productive forces of the social mind, is thus absorbed in capital as opposed to labor, and hence appears as a property of capital, more precisely, of fixed capital, to the extent that it enters into the production process as means of production in the strict sense.”

“The development of fixed capital shows the degree to which society’s general science, KNOWLEDGE, has become an immediate productive force, and hence the degree to which the conditions of the social life process itself have been brought under the control of the GENERAL INTELLECT and remolded according to it. It shows the degree to which the social productive forces are produced not merely in the form of knowledge but as immediate organs of social praxis, of the actual life process.”

The labor quantity determination of the value of commodities paradoxically comes to fruition only with the alienation of the physical and intellectual powers of the individual laborer into a social body of techno-scientific knowledge at the disposal of capital. With the eclipse of individual, ‘immediate’ labor that mentally guides the production process by a collective labor process directed by machines in which the individual is a mere cog, labor time comes to ever more minutely determine the value of output, but also loses any connection to the scale of this output. Value ceases to be the measure of use value.

“As soon as labor in its immediate form has ceased to be the great source of wealth, labor time ceases and must cease to be its measure, and therefore exchange value [must cease to be the measure] of use value. The surplus labor of the masses has ceased to be the condition for the development of general wealth, just as the non-labor of a few has ceased to be the condition for the development of the general powers of the human mind. As a result, production based upon exchange value collapses, and the immediate material production process itself is stripped of its form of indigence and antagonism.”

Marx initially thought that the phasing out of human-directed labor processes by machines would lead to a crisis in the labor quantity determination of value. In fact, it is the inevitable consequence of the increase of productivity upon which the perpetuation of capitalism depends: the first corollary of the labor theory of value, after all, is that increases in the productivity of labor expand the output of use values while the value of the augmented mass of wealth remains the same, provided the same amount of labor went into its production.

What Marx was probably attempting to explain by the cryptic formulation above was the ultimate consequences of technological progress on the level of employment. Following Ricardo, he suspected that a labor-saving pattern of productivity growth might eventually become employment reducing and this would lead to mounting problems of finding investment outlets for the freed-up capital arising out of ongoing cost-cutting rationalization, as further growth of the productive forces came up against the limits of effective demand imposed by a declining level of employment- either absolute or relative to the growth of potential output. His account of the onset of these structural limits of capitalist growth is continuous with his account of the causes of the conjunctural crises of overproduction in that the latter were assumed to recur with greater force until this elastic outer limit had been reached.

Disclaimer: This is a sponsored piece of content. Time Bulletin journalists or editorial staff were not involved in the production or writing of this content.

-

Health4 weeks ago

Health4 weeks agoShame, Trauma, and the Mind-Body Connection: How Dr. Karina Menali’s Kai Wellness Frames Emotional Healing as Integral to Physical Health

-

Startup3 weeks ago

Startup3 weeks agoDino Crnalic Discusses From Startup to 100 Employees: Leadership Lessons That Matter

-

World3 weeks ago

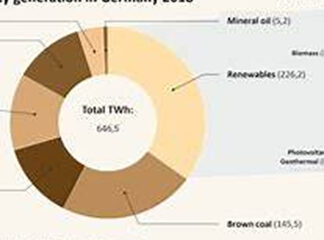

World3 weeks agoAksebe Mineralöle GmbH Accelerates Cross-Border Energy Operations Across Europe

-

Lifestyle4 weeks ago

Lifestyle4 weeks agoDr. Ankur Bindal on the Challenge of Balancing Work Demands and Family Time

-

Sports4 weeks ago

Sports4 weeks agoWhy America’s Next Major Sport Is Taking Shape Now, and Why Marcos del Pilar Is at the Center of It

-

Apps2 weeks ago

Apps2 weeks agoGoogle Introduces Gemini Enterprise App for Work on Android

-

Health2 weeks ago

Health2 weeks agoGrowing Through the Stages: Dr. Leeshe Grimes on How Mental Health Evolves from Childhood to Adulthood

-

Lifestyle3 weeks ago

Lifestyle3 weeks agoPetro Richard Kostiv: How Strategic Philanthropy Creates a Lasting Impact