World

Oil producers are pushed for an advance deal by the host of the UN climate summit

The country that produces oil and hosts the annual UN climate conference wants other oil producers to make commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but some argue that the plan is insufficient.

Some of the most reclusive state-run oil companies in the world are being pressured to lower their greenhouse gas emissions by the United Arab Emirates, which is using its influence as an oil producer and the host of the upcoming UN climate talks.

The initiative called the Global Decarbonization Alliance, is meant to make a big splash when it is announced during the COP28 negotiations in Dubai on November 30. It will likely be presented as a side event to the main conference and will not be included in the diplomatic text that nearly 200 countries’ diplomats are tasked with drafting to address climate change.

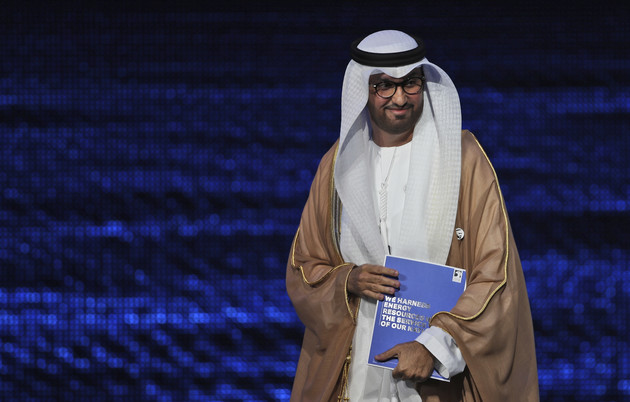

However, environmentalists who have criticized Sultan al-Jaber, the head of this year’s climate talks and the head of the national oil company of the United Arab Emirates, have already written off the effort. Rather than quickly moving away from fossil fuels, he has suggested using the industry’s vast financial resources to clean up petroleum production.

Supporters of the initiative hope to engage national oil companies—which can include major players like Saudi Aramco as well as smaller ones like Ecopetrol in Colombia—in discussions about reducing greenhouse gas emissions. These corporations, which produce half of the world’s crude and hold 90% of its oil and gas reserves, must take decisive action to prevent global temperatures from rising by 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

“Up until this point I think the [national oil companies] have not been engaged,” said Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of energy with the Environmental Defense Fund, who has been involved in discussions on the Global Decarbonization Alliance. “The COP presidency is definitely leaning into this. It is not yet clear whether the industry will respond.”

The UAE’s COP28 delegation is requesting support from national oil companies and other investor-owned companies, particularly in supporting the Paris Climate Agreement’s commitment to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, with an additional 1.5 degrees Celsius as a stretch goal. Although the pledge does not set any specific goals, companies that sign it would pledge to invest in low-carbon technologies like carbon capture and renewable energy.

Additionally, the Global Decarbonization Alliance would mandate that companies commit to reaching “near-zero” methane emissions and “aim” to reduce routine methane flaring by 2030. Given that gas traps heat 86 times more effectively than carbon dioxide over 20 years, this could result in some of the fastest benefits to global cooling.

Details may have changed as the discussions have progressed, according to the four reviewers of the document.

Proponents claim that the initiative would provide much-needed transparency to the national oil company operations, which are usually the backbone of the economies of their nations. They also hope that by applying pressure from the public and abroad—something they hardly ever encounter in their safe haven of home markets—those corporations would be forced to change the way they operate.

A COP28 spokesperson stated that 20 businesses, both national and investor-owned, have already ratified the pledge, but she declined to comment on the details of the document that POLITICO examined.

“The COP28 Presidency has called on all IOCs and NOCs to step up, align around net zero by or before 2050, zero out methane emissions, and eliminate routine flaring before the end of this decade,” the spokesperson said. “This forms part of the COP28 President’s Action Agenda to fast track a just and orderly energy transition and the need to disrupt business-as-usual and decarbonize the energy system of today while we build the low-carbon solutions of tomorrow.”

However, a lot of climate activists wrote off the document’s set of promises as just another weak instance of greenwashing by the oil and gas sector.

They argue that the UAE is duplicating existing frameworks with more stringent reporting requirements and that several major oil and gas companies have already set more ambitious climate targets. The emerging agreement drew criticism for requiring companies to attain net-zero emissions solely at their own facilities while neglecting to factor in the emissions from the production and sale of oil and gas, which is primarily responsible for the industry’s warming.

“It’s a big gaping hole,” said David Waskow, director of the World Resources Institute’s international climate initiative. “Net zero in your own operations by 2050 is not remarkable.”

In many countries with national oil companies, the public has few levers to force these companies to reduce their emissions, unlike the big players like BP or ExxonMobil who are under pressure from governments and shareholders. They are not subject to domestic competition and concentrate on increasing output to bring in money for the state.

Climate advocates are largely skeptical because of the national companies’ well-known opaqueness. Researchers at the Natural Resource Governance Institute found that only 28 out of 72 national oil companies released production data that could be verified in 2021. Not many people release their emissions data.

Furthermore, although “to measure, monitor, publicly report and independently verify” greenhouse gas emissions is stated in the Global Decarbonization Alliance document, it does not state that these actions are necessary.

The fact that the plan is being promoted by the UAE and al-Jaber is a major factor in the skepticism surrounding it. Critics argue that because he is also the CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Co., or ADNOC, the national oil company of the United Arab Emirates, he is unable to oversee the negotiations with objectivity.

Al-Jaber has introduced a few green initiatives within the organization. He has given ADNOC targets to achieve net-zero emissions by 2045 and to stop emitting the powerful greenhouse gas methane by 2030. However, the company also intends to invest $150 billion in increasing the nation’s oil and gas production capacity. That nation currently ranks seventh in the world for the production of those fuels.

The broad parameters of the Global Decarbonization Alliance include the simultaneous expansion of oil and gas production and renewable energy. For overall production to increase and the greenhouse gas emissions from that oil that are warming the planet, it calls on companies to reduce emissions intensity, or the amount of greenhouse gases associated with producing and transporting a barrel of oil, but not absolute emissions.

Furthermore, despite the pleas of environmental campaigners, it does not include targets for raising investment in renewable energy.

“There’s no reconsideration I’ve seen of their oil and gas expansion … Something’s gotta give,” said Alden Meyer, a senior associate with environmental think tank E3G. “Getting something that’s seen by many as a credible initiative that gets a share of producers’ commitment is proving difficult for the Global Decarbonization Alliance.”

Al-Jaber has made an effort to present his dual roles as ADNOC president and president of the negotiations as advantageous. He has made a point of portraying himself as a member of the national oil companies’ conservative ranks and a champion of climate action.

Al-Jaber has stated that it is “inevitable” that the world will use fewer fossil fuels. He made this claim to audiences at conferences for OPEC, the cartel of oil-producing nations to which the UAE belongs, and ADIPEC, a conference of national oil companies Abu Dhabi hosted last month.

At the Atlantic Council, Landon Derentz, senior director and Morningstar Chair for Global Energy Security, stated that the proposed oil producers’ alliance is a novel attempt at this kind of endeavor.

“The industry hasn’t been engaged structurally in any kind of consistent pattern on addressing climate emissions,” he said. “And I think that this is institutionalizing something that can credibly be returned to on a regular basis.”

-

Sports4 weeks ago

Sports4 weeks agoAl Ahly vs Inter Miami, 2025 FIFA Club World Cup – Preview, Prediction, Predicted Lineups and How to Watch

-

Health3 weeks ago

Back to Roots: Ayurveda Offers Natural Cure for Common Hair Woes

-

Tech3 weeks ago

Tech3 weeks agoFrom Soil to Silicon: The Rise of Agriculture AI and Drone Innovations in 2025

-

Startup4 weeks ago

Startup4 weeks agoHow Instagram Is Driving Global Social Media Marketing Trends

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoFIBA 3×3 World Cup 2025: Full Schedule, Preview, and How to Watch

-

Science4 days ago

Science4 days agoJuly Full Moon 2025: Everything You Should Need to Know, When and Where to See Buck Moon

-

Gadget3 weeks ago

Gadget3 weeks agoThings to Know about Samsung Galaxy S26: What’s New and What’s Next

-

Sports4 weeks ago

Sports4 weeks agoWorld Judo Championships 2025: Full Schedule, Date, Time, Key Athletes and How to Watch