Business

Amplifyou, an amazing agency for eCommerce

E-commerce has increasingly become a vital component in the emerging world of business, and a solid catalyst for economic development. Amplifyou provides Amazon automation Services which go above and beyond to generate results. It’s like a one-stop-shop that uses proprietary software to hunt down trending or in-demand products. The product they choose is sourced from a trusted supplier. This is the point when they launch, scale, and optimize their client’s Amazon store, handle all of the customer services, and provide detailed reporting of trackable revenue and finances. Internal and external, both KPIs are set and continually monitored through business planning meetings, to ensure maximum return on investment. All campaigns can be audited in seconds to ensure bigger sales using data-driven strategies for success.

It’s a leading Australian based digital advertising agency that has seen their business through a recent expansion. It has enabled them to further disrupt the eCommerce industry. At the same time, the speedy influx of new technology in the retail experience has driven clients of all ages to expect a convenient and connected experience at Amazon with their everyday lives. It is an ideal way to take your business from a traditional brick and mortar store to an innovative and well-loved brand in the market.

As everyone knows that 2020 has seen many businesses suffer from setbacks and heavy losses. The restriction on people around the world to stay at home has highlighted the need to think again about the traditional trend of business. Is it ok to go with this or business needs to be shift according to latest trend and needs? Amplfyou’s effective results-driven approach is exactly what is needed nowadays to enhance the profit of your business and avoid any kind of loss.

Mostly other Amazon automation providers shifting to other countries like Bangladesh or the Philippines to outsource their work. Clients have no other choice to pay a middleman for an inferior service that they had the ability to seek out themselves for a fraction of the cost. But on the other hand, Amplifyou has the best and experienced team to save their clients from that hassle so you don’t need to have third-party contracts in place. Their team has developed their PPC campaigns and strategies to push clients’ Amazon sales even further. Their team is based in Australia, New Zealand, the USA, and Asia, and each bringing their own strengths to the business to make it more successful. This is the thing that makes them different from others and helps them to get success in the field.

About Amplifyou:

Amplifyou is accompany based on the latest trend of business and focused on one thing which is helping other business owners and entrepreneurs from around the world with explosive growth to succeed and grow through the latest tested and proven online marketing system.

If you need a proven automated sales generating system to grow your business then you are at the right place. The team at the company is always ready to help and support the implementation of these structures which allows you to relax while they scale and grow your profit and ROI. So, if you want to grow your online business worldwide, it is a great idea to contact the expert team at Amplifyou.

-

Sports4 weeks ago

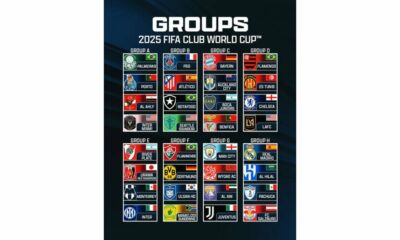

Sports4 weeks agoFIFA Club World Cup 2025: Complete List of Qualified Teams and Groups

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoAl Ahly vs Inter Miami, 2025 FIFA Club World Cup – Preview, Prediction, Predicted Lineups and How to Watch

-

Health1 week ago

Back to Roots: Ayurveda Offers Natural Cure for Common Hair Woes

-

Tech2 weeks ago

Tech2 weeks agoFrom Soil to Silicon: The Rise of Agriculture AI and Drone Innovations in 2025

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoFIVB Men’s Volleyball Nations League 2025: Full Schedule, Fixtures, Format, Teams, Pools and How to Watch

-

Science4 weeks ago

Science4 weeks agoEverything You Need to Know about Skywatching in June 2025: Full Moon, New Moon, Arietid Meteors, and Planetary Marvels

-

Startup3 weeks ago

Startup3 weeks agoHow Instagram Is Driving Global Social Media Marketing Trends

-

Television4 weeks ago

Television4 weeks agoTribeca Festival 2025: Date, Time, Lineups, Performances, Tickets and How to Watch