World

Saudi Arabia and the UAE, new Brics members, are “moving away” from the US and pursuing responsibilities in the world

The two largest economies in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were successful in their bids to join the Brics group, analysts said, strengthening their capacity to act independently of their long-standing security guarantee, the United States.

The analysts said joining Brics, a club of developing economies that formerly included South Africa, Brazil, Russia, India, and China, could also help the oil-rich Gulf monarchies’ ambitions to broaden their partnerships as they want to be recognized as major economic players.

Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt, Argentina, and the two Gulf States were also invited since the Brics group promised to support the “Global South”.

By joining the Brics, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have essentially “taken a step away” from Washington, Middle East watchers said, despite their desire to avoid being perceived as supporting an anti-West alliance.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE, according to senior resident researcher Kristin Diwan of the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, are “eager to diversify and deepen their global partnerships independent of US dominance.”

She said that they seek a “more neutral global playing field where independent sovereign countries can choose their partnerships” pragmatically and in accordance with specific interests.

According to Diwan, joining the Brics entails “taking a step away from the US and effectively strengthening the hand of China.”

On the other hand, the decision by the Brics nations to extend an invitation to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Iran to join them “highlights shifting geopolitical winds as much as it reflects an opportunity for closer economic integration with those states”, according to Jonathan Panikoff, director of the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council, a Washington think tank.

Inclusion in the Brics group is “potentially symbiotic” for Saudi Arabia and the UAE because both are seeking to engage with and strengthen collaboration with non-Western nations and diversify their economic alliances “as an additional hedge” against the US, the official added.

In a statement released by the Atlantic Council on Thursday, Panikoff stated that Riyadh and Abu Dhabi would “probably view a decision to join as furthering their goal to be viewed as not just important regional leaders, but global ones.”

As the Gulf monarchies look to aggressively diversify and develop their economies across a range of new, non-fossil fuel industries, the addition of Saudi Arabia and the UAE to the expanded Brics group would present new investment and trade opportunities to existing members.

However, analysts noted that joining the Brics is unlikely to interfere with ongoing US efforts to create a new security and economic architecture in the Middle East to make up for its shifted foreign policy focus towards controlling China and Russia.

The Abraham Accords and I2U2 groups, founded in 2020 and 2022, respectively, aim to forge strategic alliances with Washington’s friends in West Asia. The UAE is a member of both of these US-backed minilateral forums.

The Abraham Accords and I2U2 brought India into the fold and resulted in the normalization of diplomatic relations between Israel, the primary US ally in the Middle East, and four Arab countries, including the UAE.

According to Diwan, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been bolstering their economic connections in recent years by “relying on bilateral ties which provide the greatest freedom.” It is therefore “interesting” that the two states are now preparing to participate in more multilateral forums, such as the I2U2, the Abraham Accords, and now the Brics.

“I don’t think these stand opposed to each other, and, however contradictory, each may still be deployed to address particular needs and objectives,” she said.

As a result, it is unlikely that Saudi Arabia and the UAE will back Russia, their Opec-plus partner, in their efforts to turn the expanded Brics into a potent new oil lobby.

“The Russians would like to use the forum to end their isolation and to de-dollarise energy markets. But the Saudis can maintain more control through Opec and their privileged discussions with Russia,” Diwan said.

The new Middle Eastern Brics members, according to Guy Burton, an adjunct professor of international relations at the Brussels School of Governance, “will all bring different motivations and baggage.”

“The Saudis and Emiratis will see it as vindication of their growing importance in the global economy, while Egypt and Iran will be hoping that membership generates investment for their flagging economies – and Iran will see it as a potential political alliance,” he said.

“There are also the challenges of agreeing on things”, given that everything in Brics is done by consensus and there is a lack of a formal, institutionalized decision-making process,” he said.

Therefore, despite the recent de-escalation of tensions in the Persian Gulf that was supported in part by China, the Brics grouping is not anticipated to become a “vehicle for addressing ongoing disagreements among Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Iran, or indeed will resolve ongoing disagreements among the various partners”, according to Diwan.

What about Indonesia?

Observers in other parts of Asia were closely examining the potential Brics members who did not receive an invitation this time. About 40 countries were said to be interested in joining the organization before this week’s meeting. Indonesia, the country with the largest economy in Southeast Asia and the fourth most populous country in the world, was one of them.

South Africa’s ambassador to the Brics, Anil Sooklal, stated in an interview with Bloomberg that Indonesia had requested a delay in its admission so that it could consult with its Asean counterparts and that it could be admitted in two years.

Ahmad Rizky M. Umar, an expert in Indonesian foreign policy at the University of Queensland, asserted that Jakarta probably had concerns about the opinions of its neighbors in Southeast Asia.

“Several Asean member states, including the Philippines and Singapore, may dislike closer cooperation with China and Russia, so Indonesia would be taking this into consideration,” he said.

If joining Brics may benefit Indonesia’s ambitious development projects, such as the relocation of its capital city and investment in its domestic industries, particularly raw minerals like nickel, then that is of particular relevance, according to Umar.

“Brics does not provide much incentive because Indonesia is already engaging with China through the Belt and Road Initiative,” Umar said. “Jokowi [President Joko Widodo] appears to be prioritizing engaging in bilateral ties for these infrastructure projects because they might give more tangible and immediate benefits.”

According to Jefferson Ng, an associate research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, the leader of Indonesia may be seeking to defer the decision to his successor, who will take office following next year’s elections.

In any case, according to Evan Laksmana, senior fellow for Southeast Asia military modernization at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Singapore, Indonesia needed to change “its own strategic policy ecosystem to properly work around and gain benefits from new minilateral or multilateral groupings” like Brics.

The “Widodo administration’s last-ditch attempt to gain international investment and trade opportunities, rather than a systematic, well-thought-out plan to contribute to global order,” was how he said efforts to join the OECD or Brics should be viewed.

-

Sports4 weeks ago

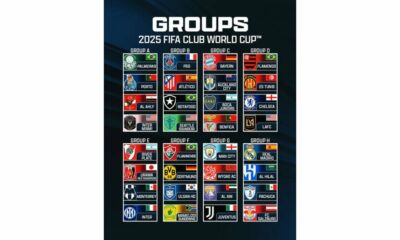

Sports4 weeks agoFIFA Club World Cup 2025: Complete List of Qualified Teams and Groups

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoAl Ahly vs Inter Miami, 2025 FIFA Club World Cup – Preview, Prediction, Predicted Lineups and How to Watch

-

Health1 week ago

Back to Roots: Ayurveda Offers Natural Cure for Common Hair Woes

-

World4 weeks ago

Omar Benjelloun: Strategic Architect Behind Major Financial Deals in the MENA Region

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoFIVB Men’s Volleyball Nations League 2025: Full Schedule, Fixtures, Format, Teams, Pools and How to Watch

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoFrom Soil to Silicon: The Rise of Agriculture AI and Drone Innovations in 2025

-

Startup2 weeks ago

Startup2 weeks agoHow Instagram Is Driving Global Social Media Marketing Trends

-

Science4 weeks ago

Science4 weeks agoEverything You Need to Know about Skywatching in June 2025: Full Moon, New Moon, Arietid Meteors, and Planetary Marvels